[ad_1]

Image from Adobe Firefly

“There were too many of us. We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and we slowly went crazy.”

Francis Ford Coppola wasn’t making a metaphor for AI companies spending too much and losing their way, but he could have been. Apocalypse Now It was an epic, but also a long, difficult and expensive project like GPT-4. I suggested that the development of LLMs attracted too much money and too much equipment. And some of the “we just invented general intelligence” hype is a bit crazy. But now it’s the turn of open source communities to do what they do best: deliver free competitive software using far less money and equipment.

OpenAI has raised $11 billion in funding, and GPT-3.5 is estimated to cost $5-$6 million per training session. We know very little about GPT-4 since OpenAI hasn’t said anything, but I think it’s safe to assume it’s not smaller than GPT-3.5. There’s a shortage of GPUs in the world right now, and – for a change – it’s not because of the latest cryptocurrency. A generative AI startup in a $100 million Series A round enjoys huge valuations when they don’t own any of the IP LLMs use to power their product. The LLM bandwagon is in high gear and the money is flowing.

It looked like the die had been cast: only deep-pocketed companies like Microsoft/OpenAI, Amazon, and Google could train models with hundreds of billions of parameters. Bigger models were considered better models. Something wrong with GPT-3? Just wait until there’s a bigger version and you’ll be fine! Smaller companies looking to compete have been forced to raise much more capital or leave the integration of goods in the ChatGPT marketplace. Academia, with even more limited research budgets, fell by the wayside.

Fortunately, smart people and open source projects have found this more of a challenge than a limitation. Stanford researchers released Alpaca, a 7-billion-parameter model whose performance approaches GPT-3.5’s 175-billion-parameter model. Lacking the resources to build a training set of the size used by OpenAI, they wisely chose to train the open source LLM, LLaMA, and instead fine-tune it to the GPT-3.5 query and output series. Essentially the model has learned what GPT-3.5 does, which turns out to be a very effective strategy for replicating its behavior.

Alpaca is licensed for non-commercial use only in both code and data, as it uses the open source non-commercial LLaMA model, and OpenAI expressly prohibits the use of its APIs to build competing products. This creates the tantalizing prospect of fine-tuning the various open source LLMs to Alpaca’s requirements and output… creating a third GPT-3.5-like model with various licensing options.

Here’s another layer of irony that all major LLMs were trained on copyrighted text and images available online and they didn’t pay a single penny to the rights holders. The companies claim a “fair use” exception to US copyright law, arguing that the use is “transformative.” However, when it comes to models built with free data, they really don’t want anyone to do the same to them. I expect this will change at the discretion of the rights holders and may end up in court at some point.

This is a separate and distinct point raised by restrictively licensed open source authors of generative AI code products such as CoPilot who object to the use of their code for training on the grounds that the license is not protected. The problem for individual open source authors is that they have to identify positions – essentially copying – and that they have done harm. And since models make it difficult to enter output code (lines of the author’s source code) and there is no economic loss (it should be free), it is much more difficult to figure things out. This is in contrast to for-profit creators (eg photographers) whose entire business model is to license/sell their work and who are represented by aggregators such as Getty Images who can show substantial copying.

Another interesting thing about LLaMA is that it came out of Meta. It was initially released only to researchers and then leaked to the world via BitTorrent. Meta is in a fundamentally different business than OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon because it’s not trying to sell you cloud services or software, and thus has a very different incentive. He has open-sourced his computing designs (OpenCompute) in the past and seen the community improve them – he understands the importance of open source.

Meta may turn out to be one of the most important open source AI contributors. Not only does it have massive resources, but it will benefit if large generative AI technology spreads: there will be more content to monetize on social media. Meta has released three other open source AI models: ImageBind (multidimensional data indexing), DINOv2 (computer vision), and Segment Anything. The latter identifies unique objects in images and is released under a highly permissive Apache license.

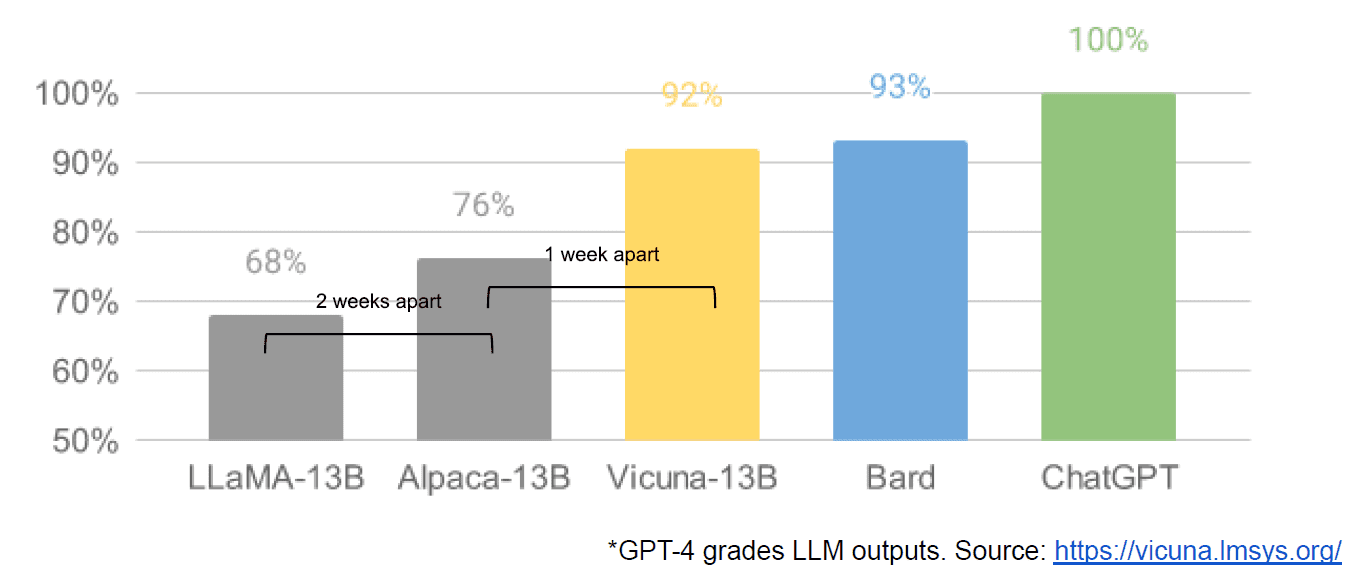

Finally, we also had the alleged leak of an internal Google document “We don’t have a moat and neither does OpenAI,” which vaguely describes closed models and the innovation of communities producing much smaller, cheaper models that perform closer or better. their closed counterparts. I say pretend because there is no way to verify the source of an article like Google internally. However, it does include this compelling graphic:

The vertical axis is the estimate of LLM outputs with GPT-4, for clarity.

Stable Diffusion, which synthesizes images from text, is another example of where open source generative AI has been able to advance faster than proprietary models. The latest iteration of this project (ControlNet) has improved it so that it exceeds the capabilities of the Dall-E2. This was due to many delays around the world, followed by a pace of progress that is difficult for any institution. Some of them have figured out how to make stable diffusion faster to train and run on cheaper hardware, allowing for shorter iteration cycles by more people.

So we’ve come full circle. Not having too much money and too much equipment has led to an insidious level of innovation for an entire society of ordinary people. What a time to be an AI developer.

Matthew Lodge is the CEO of Diffblue, an AI For Code startup. He has 25+ years of experience in product leadership at companies such as Anaconda and VMware. Lodge currently serves on the board of the Good Law Project and is Deputy Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Photographic Society.

[ad_2]

Source link